Houses of the Kings (Ali'i)

Visited January 2007

To a tourist, Hawaii's physical beauty can overwhelm

any notion of human history hidden by orchids and surfboards. But let's

explore some of that past by briefly visiting three places where kings lived.

We'll focus primarily on Hawaii's 19th century, one of those "interesting

times" of Chinese curses and the start of the latest wave of Hawaiian

immigration. That century1 saw this pre-literate

stone-age culture turn into an American territory controlled by a few white

families descendent from the missionaries who opportunistically replaced

Hawaii's defunct nature religion, first with the gospel of Jesus (first) and

then with that of Mammon.

Look below at these two "buildings": one

created at the beginning of that century and one at the end. Nothing

suggests the cultural tsunami that wiped out Hawaiian life as much as the

differences between these two structures:

|

|

|

Above is the Temple on the

Hill of the Whale: Pu'ukohola Heiau if you speak Hawaiian. The

Alexander the Great of Hawaii (called Kamehameha I) built this temple in

1790-91 by piling up tens of thousands of stones (Hawaiians had no mortar)

in order to align the gods behind his quest to unite the Hawaiian islands.

Europeans, led by the great explorer Captain Cook, had landed about 50

miles south of here a dozen years earlier. Kamehameha adopted their

metal weapons to augment the divine assistance this temple gave him.

Thirty years later, Kamehameha's son and successor would rule the Hawaiian

religion that inspired this edifice was null and void.... |

...Contrast with the 'Iolani

Palace above -- the only Royal Palace in the United States.

Completed in 1882 after the Kamehameha's descendents traveled to Europe to

see how their fellow royalty lived, it had electricity, phones, and many

other modern accoutrements even before Washington D.C's White House.

On the left, we have the results of the greatest Hawaiian king leading his

men to create a stone-age religious structure. At right a

secularized state-of-the-art Victorian-era residence inspired by

Renaissance architecture. Get out your reading glasses and

examine the flag flying at half mast.3 They'll be a quiz

later. |

But before we discuss either of the above edifices, let's start

with the Hawaii before it was "discovered" by the Europeans (whom the

Hawaiian called haole which means "no breath" because they

assumed anyone with such a pale appearance must have respiratory problems).

To illustrate this we'll go to Pu'uhonua o Honaunau where the National Park

Service has restored/reconstructed a royal village complete with temples and a

sanctuary spot.

The Royal Village at Honaunau Bay

|

Pu'uhonua o Honaunau is a 420 acre archeological site near where

Captain Cook was killed. Ironically, he died because of a

cultural misunderstanding. When Hawaiians met strangers, they

offered food. If you ate it, you were obligated to share your

possessions with the Hawaiians. What Hawaiian culture called

sharing, Europeans considered to be stealing. After this horrible

failure to communicate, Cook laid dead. (His bones may have been

interred at this temple). The Europeans retaliated not so much with

war, but with disease which wiped out 80% of the natives in the ensuing

years. The second king and queen of Hawaii traveled to London where

they contracted measles and died. Cook, you are avenged.

Ancient Hawaiians had no nails -- or any other metal for that matter.

So here's how they built their royal abodes with sticks and stones: |

|

|

Above left is a half-size framework of a temple/mausoleum using branches from

the common 'ohi'a tree tied with coconut-fiber. The thatching uses leaves

from the Ti plant. This construction is typical of Hawaiian houses.

Without nails and mortar, no palaces could be built, so the residences of kings

were typically collections of these buildings (typically ten or more)2

in royal compounds. Certain commoner Hawaiians would specialize in trades

such as weaving thatch roofs. They'd learn this from their parents,

practice it all their lives, and teach it to their children. Below are more

photos from a larger building on this site:

Was this a palace fit for a king? Judging from the Iolani palace

pictured near the top of the page, royal residence construction came a long way

in a short time.

Without nails or other metal fastenings, the length of the trees pretty well

limited the size of Hawaiian abodes, even those for kings (which were typically

larger than those of commoners and were constructed on top of lava-stone

platforms). But even a king's home was small as lava flows often limited

the height of trees. (By the time trees got big, a periodic lava eruption

would destroy them.) Below is one of the larger huts, big enough to

contains an outrigger canoe made from the Koa tree.

Every building

was, essentially, a one-room hut. Kings would have several of these.

This area thrived when the Hawaiian feudal system was at its peak and each

island had its own (sometimes several) kings. This particular compound

held the kings (called Ali'i) of the South Kona ahupua'a

(called Honaunau). Kona is now the hub of tourist life on the west side of

the big island. Hawaiians

divided their mountainous islands into pieces of pie called ahupua'a,

with a king (Ali'i) over each slice. This political/social entity would

start in the mountains and follow the river (and its valley) to the shore,

allowing residents to barter their fish, agricultural products, and fresh water

with fellow members of the ahupua'a. This allowed resources to be shared

rather than competed over and was good for the land and the people (even though

the king owned all the land and so the commoners had to provide him with fairly

heavy amounts of their produce).

The Temple (Heiau)

Besides residences, royal sites such as here, the capital of the Honaunau

ahupua'a, would contain temples, called Heiaus.

These would be raised stone platforms topped by other structures such as houses

(serving to inter the bodies of kings), various carved icons (called ki'i), and

altars for sacrifice (including humans). Most of the Heiaus disappeared

after the death of the Hawaiian religion in 1819 and were plowed under to grow

sugar cane. Here at Honaunau, the National Park Service has reconstructed

the Heiau which held the bones of an important 16th century Kona chief named

Keawe along with 22 others, possibly including England's Captain Cook who was

killed about 4 miles north

of here. Some remains would be put in wicker caskets in anthropomorphic

shapes.

Here's some photos of the Heiau:

To the right is a platform (larger picture below) used to place the offerings

to the gods. You boy scouts undoubtedly remember building these in summer

camp but always wondered what they might be used for besides earning pioneering

merit badge. Human sacrifice, as I recall, was forbidden by scout leaders

by then.

Surrounding the Heiau are many wooden carvings of the gods (called Ki'i).

Typically these face the shore from whence the enemy would arrive.

Remember your back is to the mountains and everyone between you and the mountain

peaks is in your political slice of the ahupua'a pie. The enemy approached

via the sea.

Pu'uhonua o Honaunau

Besides houses for royalty (OK, really thatched huts) and temples, this site

also contained a place of sanctuary -- a refuge for warriors too injured to

fight or who were defeated and for those who violated the kapu (taboo).

This sanctuary is called a Pu'uhonua. Kapu (taboo) was a set of

religious prohibitions with a single punishment -- death. The theory

was that certain forbidden behavior (like men eating with women) could bring

down the indiscriminate wrath of the gods upon the whole population (e.g., a

tsunami, volcano eruption, whatever -- Hawaii has no shortage of natural

disasters in search of pre-scientific explanation.). Therefore anyone who

violated a kapu should be killed so the gods would be appeased before they

started their wholesale fire-and-brimstone from a conveniently placed volcano..

This is pretty hard to refute if you enforce it consistently. Somebody

violates kapu, you kill them, and no natural disasters happen. Besides

dictating with whom you could eat (men with men, women with women, not unlike a

grown-up junior high cafeteria), kapus governed what food could be eaten, and

what interactions commoners could have with their chiefs. (For example, if

your shadow fell on a chief, you got to be sacrificed. Today, we'd make

them work for Dick Cheney.)

There was an exception to all of this. If you violated kapu and could

get to a place of sanctuary, priests (kahunas) could perform cleansing

ceremonies to appease the gods and you would be allowed to live. To keep

this from happening often, the barriers to the sanctuaries (called pu'uhonua)

were rigorous. To get to the safety of the Pu'uhonua o Honaunau, you'd

have to swim a long way through treacherous waves smashing into jagged lava rock

as the Hawaiians had constructed the impenetrable fence below to bar land

access:

This 10' and 17' thick wall of Pahoehoe

lava separates the royal village from the sanctuary -- and the kapu violators

from their forgiveness. It runs in a large "L" --600' in one

direction and 400' in the other enclosing about 5 acres between it and the

ocean. Some of the rocks here are over 1000 pounds and were probably moved

with the help of pry

bars.

Kapu works fine as long as everyone believes in it, somewhat like wearing

green glasses in Oz. But when foreigners poured into Hawaii and ignored

kapu and no natural disasters followed, the belief system was shattered by

reality. That's what happened for about forty years from the time Captain

Cook opened the islands to the Westerners and their rowdy sailors pretty well

flaunted kapu, spread disease among the natives, and pretty much did what they

thought sailors had a right to do during shore leave. So the inevitable

happened: Kapu fell when a king decided to eat with women and the gods did not

strike him dead. Unfortunately, this was not the king's conversion to a

new religion with a replacement set of moral standards -- but an abandonment of

a set of laws that permeated daily life. For the first year after kapu was

kaput, the Hawaiians had no religion and havoc prevailed. Sodom and

Gomorrah ended when the Congregational Christians appeared shortly thereafter

and converted some of the royalty. Walls such as the above were torn

down, in more ways than one.

To see more photos of the the Pu'uhonua o Honaunau and further explore

ancient Hawaiian life, click

here.

Pu'ukohola Heiau

The Royal village and sanctuary at Pu'uhonua o Honaunau, though, represents

the quieter time before the European sailors' behavior destroyed the Hawaiian

religion and the American missionaries replaced it. Let's return to the

first picture on this page, another pile of stones (and temple) called the

Pu'ukohola Heiau found north of Kona on the dry side of the Big Island. In

fact, this is one of the most dry places

in the United States, getting only 10 inches per year.

At least three temples (Heiau) have graced this traditional Hawaiian

religious site. Two are still visible. The one below is of the

smaller and older Mailekini Heiau.

This was probably built by one of the chiefs who ruled over a section of the

island and was typical of the temples in that it had a high wall on the mountain

side but a low wall facing the sea so the enemy approaching in war canoes could

see over the wall toward the temple buildings. Like the ancient Greeks,

the Hawaiians were using imposing temples to convince the enemy not to mess with

a local population favored by the gods.

More than anywhere else in Hawaii, this ancient site is probably where the

stone age met the modern world and aggressively embraced its deadly technology.

Within a generation, Kamehameha and western weapons would unite the islands for

the first time. Negotiations and delivery would often occur here,

typically with the assistance of an English seaman named John Young who was

accidentally left behind by his ship -- and stayed here until his death at age

93. He intermarried with Kamehameha's royal family and a granddaughter

become the very popular Hawaiian Queen Emma.

Young became a trusted ally of Kamehameha who, in turn, made him governor of

the Big Island. If westerners wanted to trade with Hawaiians, they first

had to stop here and negotiate

terms with Young who lived here in a western style house created with stone and

mortar. By 1819, Young installed 21

cannons on the temple rise of Mailekini Heiau. . His western-style

home was located among the trees shown in these pictures. (An 1819 map

shows about 90

structures in the area.) The location of his house was no accident as

these same trees contained the royal village of Pelakane. Despite

Pelakane's significance (it was here that Kamehameha killed a rival Hawaiian

king and solidified his control over the Big Island), nothing is left here but

the ground and scrub trees and bushes growing in this most dry place of lush

Hawaii.

|

Just beyond the old temple/fort is the port of Kawaihae

which contains, among other things, a military landing site. (Kawaihae

literally means "water of wrath" in reference to the many wars

fought over the source of drinking water here.) The picture at left

looks beyond the eastern edge of Mailekini Heiau toward a small harbor

built just below the larger harbor in this picture by Project Tugboat --

an atomic swords-to-plowshares effort of the Atomic Energy Commission.

The idea behind Tugboat

was to use small nuclear explosions to blast out harbors in the tough

volcanic rock. Nuclear weapons were not used here; instead 100 tons

of chemical explosives -- about the size of the smallest nuclear weapon's

impact -- were buried in the reef and blasted out the harbor.

Tugboat did not move beyond the proof-of-concept stage. What if

nuclear explosives really had been used to create a light draft harbor for

pleasure craft? If so, this spot where the stone age moved to

European bronze weapons would have come full cycle into the atomic age.

John Young, what have you started!

Besides Young, Kamehameha lived here while consolidating his power.

Upon his death, his son returned here to plan his next steps.

But as the best

harbor in old Hawaii, not just weapons arrived here. George

Vancouver brought Hawaii's first cattle.

Others introduced horses to the islands here. The export that

made Kamehameha rich was sandalwood and its trade centered here as well as

the natives were forced ever deeper into the center of the island to

denude its forests. Eventually the Vancouver's cattle were exported

from the nearby Parker ranch. Much, much later, portions of the

movie Waterworld

were filmed here. |

If we look directly back from the viewpoint of the harbor at upper left, we

see one of the last temple built (1790-91) by Kamehameha when the Hawaiians

relied more on the favor of their gods than on the the cannons of the West. Kamehameha

was the leader of the western side of the Big Island which, because of its

better harbors, had more exposure to the Europeans and their metal and guns.

He adopted their technology quickly, aided by John Young. This gave him a

strategic edge over the chiefs he would subjugate. But mother nature

helped too when his arch-enemy Keoua's army was destroyed on the other side of

the island by an unexpected eruption of volcano Kilauea. This not only

wiped out part of Keoua's force, but made neutral folks think the gods

favored Kamehameha.

|

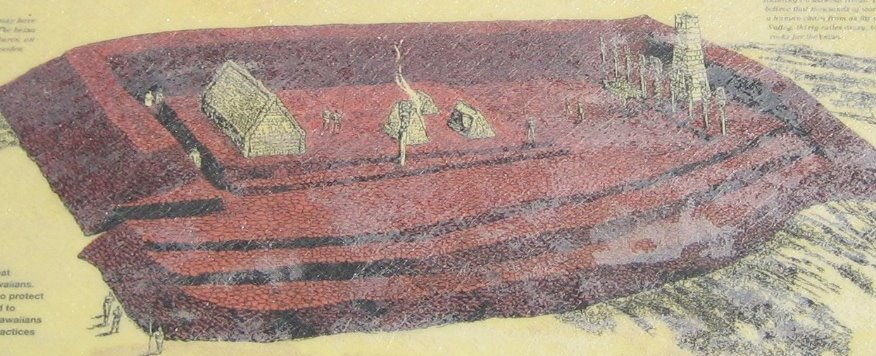

At the top of this page, we showed a photo of the Temple on the Hill of

the Whale called Pu'ukohola Heiau. At right is an artist's

interpretation taken from a sign the National Park Services has erected at

this site. Only the priests (kahunas) and some select royalty would

be allowed beyond the stones.

Kamehameha built this temple very quickly (1790-1791) after a seer had

prophesied that if he built a temple to the war god Ku here, he would win

battles that would allow him to unite the Hawaiian islands. Up

until this point, he had fought long and hard but was still far from

achieving his dream of uniting the islands. When he attacked Maui,

chiefs left behind on the Big Island would revolt against him and he'd

have to return and start over. The prophecy was worth a try.

When weapons fail, petition the gods..

|

- "The major advances in civilization

are processes which all but wreck the societies in which they

occur." --- Alfred North Whitehead4

|

All were drafted into the construction and even chiefs (including Kamehameha)

helped lift stones. The

priest/kahunas were everywhere to plot the site and offer rituals and human

sacrifice at key points. During construction, subjugated chiefs on the

other islands attempted an invasion of the Big Island in the hope that they

could disrupt the construction. By this point (1791), both sides

were armed with cannons on war canoes. This was the first and last

Hawaiian naval battle fought with gunpowder and canoes. Kamehameha, with

his weaponry commanded by John Young, prevailed. Kamehameha then

returned to completing his temple:

|

Above is Kamehameha's Pu'ukohola Heiau -- essentially three tall

mortar-less walls made up of lava rocks with edges rounded by water. The

long sides are 224' and the ends about 100'. These are about 12'

wide at the base but narrowed to 6' as they rose 20' into the blue Hawaiian sky.

Essentially, the walls are stacks of rocks siting atop earthquake faults.

The side nearest the ocean is low (7' to 8'), allowing those approaching by sea

to see the thatched huts and other worship paraphernalia within. While it

may not impress modern tourists (we were one of only about three groups

wandering the earthquake-damaged site on a mid-week January morning), the temple

worked its magic and gave Kamehameha his dream. Shortly after the temple's

completion, Kamehameha's only significant opposition, the rival Big Island chief

Keoua and his retinue visited the temple and found themselves to be human sacrifices

to inaugurate the temple. Kamehameha now controlled the Big Island.

Three years later (1795) the islands of Maui, Lana'i, Moloka'i, and Oahu were

his through war. Kauai was his without a fight -- but not until 1810.

He ruled for another 9 years.

In its 3 decades, this was a powerful religious place.

The stone walls were topped by a wooden rail with spikes holding skulls of those

sacrificed within. (Kamehameha eventually banned human sacrifice.)

Five huts inside housed kahunas (priests). Later explorers describes roofs

which appear white when approaching the temple by sea -- but turn out to be

human skulls.

Accounts at the time of Kamehameha's death (1819) describe the walls as

containing at least 40 large statues (Iki). Many of these would be to

Kamehameha's favorite deity, the war god Ku who was thought to occasionally

reside here. Only priests would be allowed inside the temple. They

would predict the future by examining the entrails of victims. The ground

would be littered with the ashes and bones of previous sacrifices. While

this may seem gruesome, Hawaiian kings felt it necessary to show their power and

their ruthlessness in maintaining it.

Kamehameha established the Hawaiian kingdom by exploiting its ancient

religion and the new weaponry of the West. Upon his death, the religion

that delivered him his power spun apart and holy sites such as Pu'ukohola Heiau

were abandoned, if not destroyed. Nine years later his queen visited the

site of the abandoned temple for the first time, since the laws of kapu forbade

women from approaching a temple under penalty of death. Her reaction was:

"I thank God for what my eyes now see . . . Hawaii's gods are no

more."

The site lives on at a fairly low maintenance level. The National Park

Service took over the site in 1972 and provides a small visitor center, a map, a

few signs, but not much else. They did remove some communication equipment

from the Heiau's days as a WWII lookout

station. An October 2006 earthquake damaged portions of both Pu'ukohola

Heiau and the smaller Mailekini Heiau, causing the closing of both. Modern

resurgence of interest in ancient Hawaiian ways brings rituals and sacrifices

back to these temples during native festivals.

|

There is another temple at this site, but no one has seen it recently.

It's the temple to the shark gods called Hale o Kapuni Heiau. Chiefs

believed that their ancestors could become physically present within

certain species

and would appear to them in times of distress. An early chief at

this site revered sharks and built a submerged temple to them as sharks

frequented this bay. Hawaiian royalty also made sport of catching

sharks in nooses and would feed them routinely so they would be available

when the hunt began. Today, signs caution against wading here.

The temple may have once risen above the water line about two feet

during low tide. However, rising water levels and silt from the

nearby harbor reconstruction (Thank you, Corps of Engineers), has obscured

its location.

At left is a picture of the shark bay in the distance. About the

middle of the picture is a stone used by a chief named Alapai who

would watch the sharks as they devoured his sacrifices (sometimes of human

flesh). Hawaiians had no chairs and sat on the ground so this stone

would be a backrest. The stone broke in 3 pieces in 1937 when a truck

backed into it. Such are the vagaries of Hawaiian archeology.

For more pictures taken at this site, click

here. |

'Iolani Palace

This brings us to our third (and final) residence of the Hawaiian Kings, the

'Iolani Palace, built in 1882 -- 90 years after Kamehameha petitioned the war

god Ku by erecting his mortar-less stone temple. Compared with

palaces in Europe (where Hawaiian kings traveled to meet their peers and acquire

Western taste), 'Iolani was small-but state-of-the-art. Hawaiian kings had

come a long way -- but didn't have far to go as the monarchy was overthrown 11

years later in 1893.

A good sign that an institution is in decline is an edifice complex. We

in Houston have our grand new

Enron building. Rome built St. Peter's Basilica as the

Reformation gained steam. Downtown Honolulu has the 'Iolani Palace, which

became a prison for the last Hawaiian monarch, Queen

Lili`uokalani. The Hawaiian monarchy was slow to rise and quick to

fall. All of Hawaii was united in a single kingdom in 1810. A

succession of constitutions gradually made the monarchy more limited until the

infamous 1887 "bayonet

constitution" took power away from not only the king, but pretty

much everyone except for a wealthy elite. Ten years before it

crashed, the Hawaiian kingdom created its Royal Palace.

For our January visit, the palace was

still wearing its Christmas decorations. Above is a square

convex-edged campanile tower common to renaissance Italian architecture.

(The palace is said to be the only example of American

Florentine architecture.) Here's some of the exterior details (

If the building looks familiar, it may be that you remember its use on

Hawaii 5-0 as a police station. (It never was a police station but

was the state capitol until the larger Bauhaus style capitol

building was completed directly behind the 'Iolani Palace in 1969.) |

|

Built in about 2 1/2 years, the palace

build quickly went through two architects before settling on Isaac Moore who had

made his name in Honolulu as a woodworker.99

Therefore it's no coincidence that the interior is finished in ornate Hawaiian

and North American wood. But that's not all, the palace was a marvel of

modern conveniences in the 1890s:

- The residential second floor

had four bathtubs including the King's tub which was 7 feet long.

(Hawaiian royalty were large people).

- Sinks were set in marble

slabs and complemented by nickel-plated faucets

- The attic contained four

200-gallon galvanized tanks to power all of this; these, in turn,

were connected to the municipal water supply which in 1850 forever

rescued Honolulu from its dessert-like water shortage102.

- The high ceilings (18' on

the first floor, 14' on the second99)

were graced with gas-lit chandeliers (300 burners in all) which were

eventually replaced with electric power. Given Hawaiian

climate, no further furnace work was required.

- Two phone lines were

installed including one from the King's bedroom to the Queen's.99

(Was this the invention of phone sex?)

- Of course the place had a

dumb waiter, now standard in most Houston restaurants.

(Unfortunately, picture taking was kapu inside 'Iolani Palace -- but the

palace's web site will show you the interior

by clicking here).

During the days of the last monarchs, the palace contained the sophisticated

clutter characteristic of the homes of wealthy Victorians. Today it's

rather bare -- signs request those that have artifacts from the original palace

to return them. Check your attic! An audio tour guides visitors

through the first floor public rooms and second floor royal living area

including a music room. (The Hawaiian anthem is one of Queen Lili`uokalani

's 165 compositions.)

The queen's bedroom sports a quilt supposedly created by her during her 5 month

imprisonment. The basement is also open for browsing.

The monarchy had come a long way from the grass huts of its founder,

Kamehameha I. After moving from his preferred location near Kailua/Kona on

the Big Island, he tried living in a brick building erected for him in Lahaina

on Maui but never quite got used to it. Eventually he moved his capital to

Honolulu as foreign traders loved this Oahu port.

Next door to the Iolani Palace is the barracks:

Built in 1870, the barracks housed the palace guard in a medieval-castle

inspired building made of coral limestone blocks. It was moved to this

site to make room for the new state capitol building. It has had

many uses over the years including housing the National Guard. Today it

contains a gift shop (what else?) You can also rent it for a luncheon

or a wine-tasting. Hawaii has come a long way from Kamehameha's days when

a commoner would be killed if his shadow fell on the king! (See Mammon

above).

The king is dead, long live the king

There are two items we saw during on the Iolani Palace grounds that we've

left out of these pictures: the tent and the flag. Let's start with the

flag:

If you look closely at the top picture of the palace, you'll see the British

Union Jack flying at half mast. (It's not really a British flag3

but that of the state of Hawaii --called Ka

Hae Hawaii.)

If you didn't know that Hawaii was once a British Protectorate, you don't know

Jack. In its early years, the Hawaiian kingdom was closely allied to

England before they discovered that the sugar trade with the States was the key

to making the select few rich. (It brought elitist prosperity to the

islands which paid for the construction of this palace).

Why no American flag? Well now the story of Hawaii's kings takes a bit

of a post-modern twist. A century after the monarchy ended with Queen

Lili`uokalani 's overthrow by American planters, the US Congress passed the Apology

Resolution. (Remember those thrilling days of yesteryear

when the President could feel your pain? Are we really better off with

that Lone Ranger that succeeded him? Let's not go there.) The

1993 Apology Resolution did just that -- apologized for the role the US played

in the overthrow of the monarchy.

The Apology Resolution injected considerable energy into the Hawaiian

Sovereignty Movement -- a loose collection of groups with solutions ranging

from giving Hawaiians some of the legal structure of Native Americans in the

other 49 states all the way up to full independence ala the Québecois

"nation." The 'Iolani Palace has become a symbol for the

movement and now only flies the flag of the state of Hawaii which is also the

flag that over 70 nations recognized as the standard of the Hawaiian monarchy.

And the tent? The tent was the first of many that would sprout on

Palace grounds the week we were there. They would shelter demonstrators

taking advantage of the Martin Luther King holiday weekend to protest in favor

of Hawaiian Sovereignty, wherever that will lead. Two centuries before,

Kamehameha sat in his grass hut, not much different in shape, function, and

amenities from those tents, dreaming of the monarchy that was to come.

In case you missed them accidentally, here's a summary of the links to our

other pictures for these three sites:

- Pu'uhonua o Honaunau (the sanctuary with the royal village and

temple), click

here.

- Pu'ukohola Heiau (the large temple built by Kamehameha to

conquer/unite all Hawaii), click

here.

- 'Iolani Palace, click

here

For an index of all of our Hawaii pictures, click

here

Created on 19 March 2007

Notes:

1 OK, my math isn't exact. I'm using the

"century" that begins with 1790 and ends in 1882 -- but you get my

drift.

2 Unless otherwise stated, information on

Pu'uhonua o Honaunau is from the National Park Service publication

GPO:2006-320-369/00417 distributed at the site entrance. Most of the

information in the linked photo shore is also from this publication or from our

pals at Wikipedia.

3The flag was flying at half-mast during the 30-day

mourning period for former president, and University of Michigan Alumni Gerald

Ford

4 "I have suffered a great deal from writers who

have quoted this or that sentence of mine either out of its context or in

juxtaposition to some incongruous matter which quite distorted my meaning , or

destroyed it altogether." ---Alfred North Whitehead

This

work is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.