Above is a diagram of the earthernwork section found to the

west. The turf wall was 30

feet thick at its base.

Above is a diagram of the earthernwork section found to the

west. The turf wall was 30

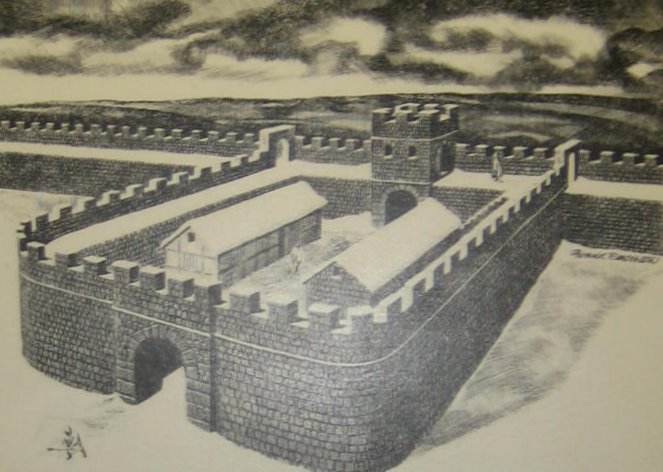

feet thick at its base.Before talking about Housesteads Fort, let's talk about the fortifications that this fort (and fifteen others) supported: Hadrian's Wall. Lacking a natural boundary to keep out the riff-raff, the Romans built this wall along the narrowest part of northern Britain between two rivers. Below is a picture of the "narrow" wall reaching eastward from Housesteads Fort. The remains of a gate show in the middle of the picture. We'll talk about that gate later.

Built along an existing Roman road called Stanegate (which was protected by several forts built a days march apart) Hadrian's wall marked the northwestern extent of the Roman Empire: beyond were the barbarians. South of this wall, Roman rule brought a common currency and roads (earlier tribes resisted roads as their isolation was their best defense from other tribes). The combination made trade blossom. No one kills his customers and so peace ruled. North of the wall, the tribes/clans flourished. Even to this day, the Scottish history, culture and customs differ from those of England -- some of that is due to this stone and earth belt cinched across Britain's high waist between the River Tynne and Solway Firth.

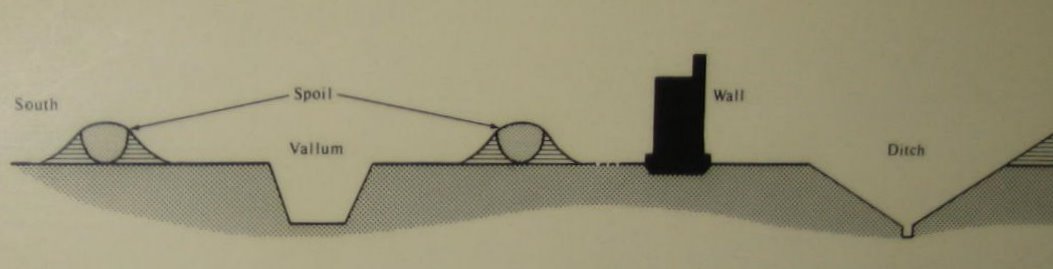

The wall itself ran 80 Roman miles (73.5 modern miles) and was made of stone in the East and earthwork in the west. The wall was the highest of a wide set of fortifications diagrammed above. Separating civilization (to the south) from barbarianism (to the north) were two high 33-foot-wide berms formed by digging a 30 foot wide by 10 ft deep ditch (called a vallum) between them. The berms served as a highway until the Romans added a road linking the milecastles called the Military Way. Next came the wall itself -- 16 to 20 feet tall and whitewashed to look even more ominous to the barbarians. On the enemy side (north) was another ditch, 30 feet wide and 9 feet deep with a false bottom holding spikes.

This fortification evolved from the defenses of an army on the march. Even while under attack, Roman engineers and soldiers could dig a trench around a large rectangle. The earth from the ditch would be thrown inside, creating simultaneously a dry moat and an earthen wall. Roman soldiers would carry 3 or 4 tree branches (the word vallum means stake in Latin). These stakes each would have from 1 to 3 branches and would be "planted" on top of the earthen barrier, forming an immediate palisade. Thus the soldiers would have an immediate refuge for the night. If the fort was to become permanent, the stakes would be replaced by stones.

The slight creek, bristling with weeds, seen to the right of the wall in the middle of the picture is significant. It's Knag Burn and it supplied water to the fort and a Roman bath (long disappeared) nearby. Without this water source, the fort would have been placed elsewhere. The rectangular remains just beyond are the remnants of a gate added in the 4th century after the north gate inside the fort was abandoned as its approach up the cliff was too steep for wagons.

Were looking at the "narrow" wall, about 8 feet wide. The ditches and berms along each side have long disappeared from here but the vallum ditch can be seen a few miles on either side of Housesteads Fort [39]. The wall was originally planned to be 10 feet wide but narrowed in most places to 7 to 8 feet. Construction started around 122 AD when Emperor Hadrian decided his predecessor had conquered more territory than Rome could hold. In most cases, the Romans had stopped at natural boundaries such as mountains and rivers. In northern England and parts of Germany, no such boundaries existed. Therefore the Romans created a huge wooden wall with all those German trees. Lacking suitable wood here, the Romans quarried limestone in the east and moved earth in the west.

|

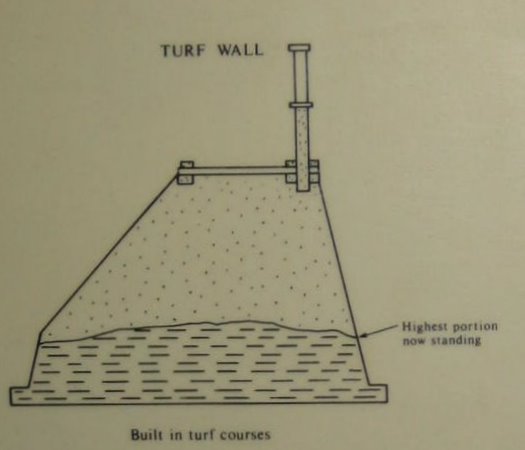

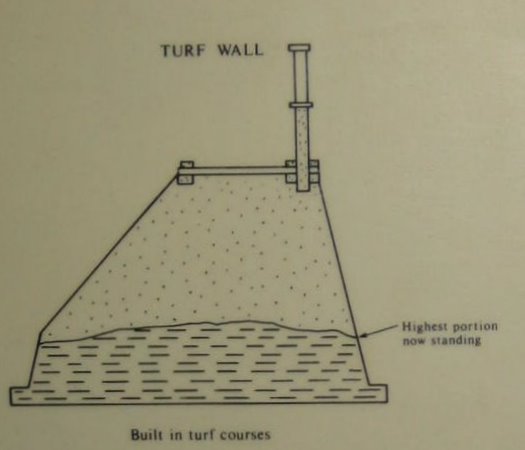

At left (complements of the museum on site at Housesteads) is a diagram of the narrow wall. The exterior walls were made of quartz from quarries near Manchester and the rubble between them came from small quarries near the wall. |  Above is a diagram of the earthernwork section found to the

west. The turf wall was 30

feet thick at its base.

Above is a diagram of the earthernwork section found to the

west. The turf wall was 30

feet thick at its base. |

The wall was built by three Roman legions made up of Roman citizens -- sort of like our army corps of engineers. After completion, staffing was turned over to the "B team" -- soldiers from the provinces called auxiliaries.

Besides the walls itself, several other components were required to defend the south. The Roman legions built a milecastle and 2 signal turrets every mile so soldiers were never more than 1/3 mile from each other, well within sight (and a quick run to spread the message) during the day; at night, a series of signal fires could quickly communicate a pending attack. Here's two museum pictures of a typical turret (the design was different for each of the 3 building legions.

|

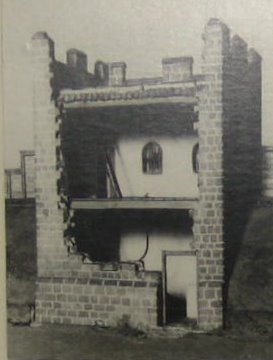

The turrets were built with "wing walls" to connect to the wall which was built a little later after all the turrets and milecastles were finished [39]. Turrets had two inside stories, measuring 14 feet square inside and 20 feet square outside (those are thick walls!) Ladders led up the stairs and each turret contained a hearth, water tank, and glazed windows. In Housesteads' case, the original turret was torn down when the Romans decided to put a fort at its position on the wall.

Besides the two turrets, each mile contained a milecastle (see below) made from one of three designs depending upon which legion built it). These would house about a dozen troops who would also staff the signal turrets nearby. Depending upon the construction of the walls, milecastles would be built with either stones or turf. Turrets were always built with stone (try stacking earth that high!) About 10,000 soldiers were required to staff the wall fortifications and they created a local economy of services along the southern side of the wall.

Do good fences make good neighbors? When completed, Hadrian's wall was the empire's most expensive undertaking, taking about ten years to build. In general, it kept the pesky Picts at bay. Hadrian's successor, Antonius Pius built a similar wall to the North about 100 miles called (what else) the Antonine Wall. It was abandoned 20 years later when Marcus Aurelius succeeded Antonius and determined that the wall would never hold the local population at bay.

By contrast, Hadrian's wall enabled Rome to rule to its south for nearly 300 years. (The somewhat United States have been around almost that long). Troops stationed on the wall were trained to fight in the open as the Romans did not anticipate an assault on the walls. Rather they would engage the enemy in the open field after identifying the area of the invasion. (By contrast, the Great Wall of China failed because the enemy on horseback could move faster than the wall's defenders.) Hadrian's wall survived major attacks in 180 AD and in 196/197AD, causing refortification in some areas. It outlasted the Roman empire although much of the wall disappeared as its stones were re-missioned for other building projects in the area. Today, Hadrian's Wall Path National Trail, allows tourists to hike this line or fortifications, some long disappeared.

![]()

This

work is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.